I just got off the phone with my friend Justin.

Yes, I have a standing weekly meeting with him at 7 AM on Tuesdays. Yes, I’m insane.

He reminded me of another one of those lessons that I keep relearning.

It’s about optimization.

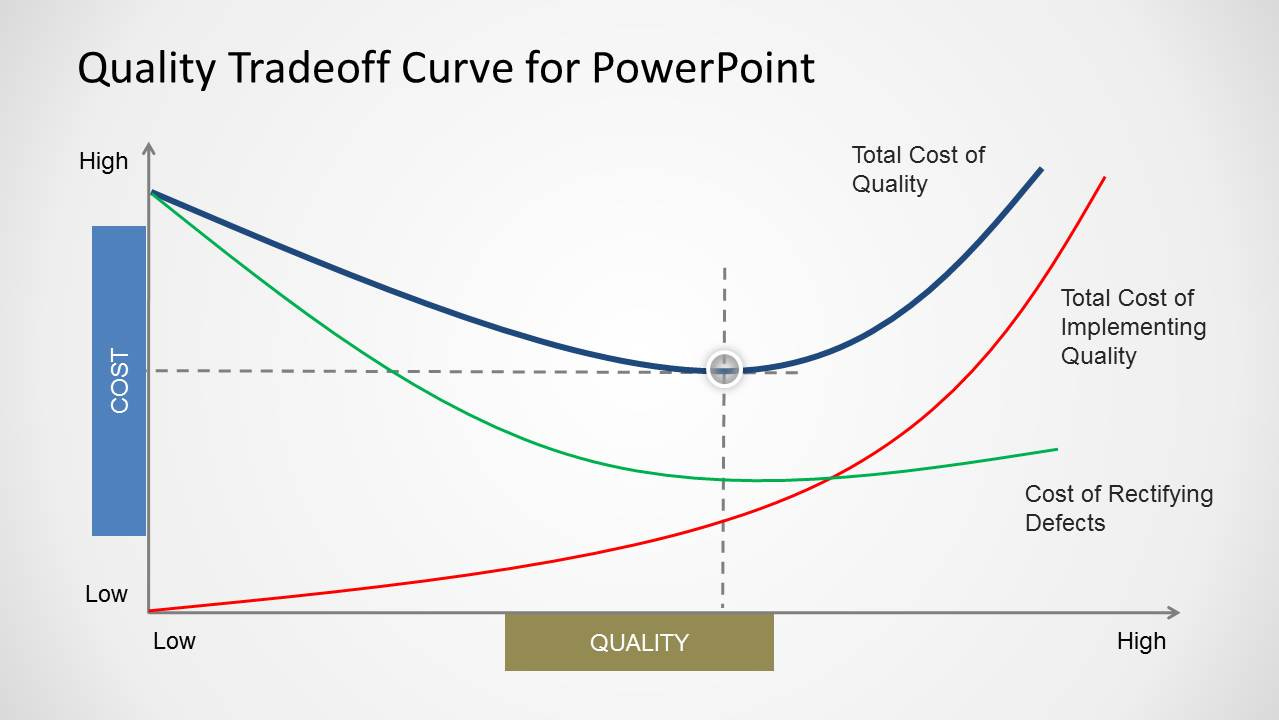

A few years ago, I worked with a software team. We were making some super high-tech software for some classified government clients. It was all about data and visually representing data so that non-technical stakeholders could make smart decisions.

Basically, we were able to account for several factors all at once and make a chart that a decision-maker could read and actually see the tradeoffs they were about to make. From there, they could decide what options were acceptable and which weren’t.

The only trouble is that, inevitably, decision-makers realized that they couldn’t have everything they wanted. It couldn’t be fast, cheap, and sustainable. You just couldn’t make the solution all three. You had to choose what you valued most and accept the tradeoff on the other dimensions.

As unpleasant as this was, it was the reality and decision-makers accepted it.

In the end, knowing that there was no magic option (where they could have everything they wanted) allowed them to be happy with the decision they made.

This is huge.

Don’t miss this point.

By understanding all the options and seeing what was possible or impossible, they were able to be happy with their decision.

This is not a luxury we get in life all the time.

Tell me if this resonates with you:

“I wonder if I could have gotten the salesman to drop the price lower.”

“I wonder if I could have made more impact.”

“I wonder if I could have managed that situation better.”

We never know what all the options are. We never know what the upper limit is. We never know if we made the “right” choice. This makes us unsettlingly unhappy with our decisions.

If only we had a nice chart to plot our futures. Oh, well.

The point here is that it’s up to us to do our best with the information we have and give ourselves permission to be sub-optimal.

We’re never going to be able to optimize our careers so that we can get paid a million dollars, do maximally impactful work, do work we’re really good at, and do work we love to do.

That’s too many variables. That’s too many dimensions for which to optimize.

It’s just not feasible to put that much pressure on your career, job, relationship, or whatever thing it is you’re trying to optimize in all directions.

So, what do we do?

We pick the things we value most, we do our best to meet those standards, and we accept the trade-offs.

Besides, that’s why we have hobbies, friends, and side-projects. They’re wonderful supplements for our other work.

I hope this helps you evaluate your decisions with a little more practicality, a little more feasibility, and a little more forgiveness. In the end, what we’re really shooting for is happiness—and it’s just too easy to get caught up in optimization.

It reminds me of of a line from Victor Fankl's book 'Man Search for Meaning': "

"When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves." (E.g. you could substitute the word 'change' for 'optimize', opening another dimension of opportunities in the face of unavoidable tradeoffs).

As a side note on the closing remark of your excellent post ("we're really shooting for happiness"), I think I agree with Frankl that happiness, like success, in themselves are not realistic pursuits, but rather to pursue what is meaningful.

As he eloquently says: "Don't aim at success. The more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one's personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one's surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that in the long-run—in the long-run, I say!—success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think about it."