Lazy Skepticism

Infinite regression, turtles, Sherlock Holmes, and The Big Lebowski

When I was studying philosophy in college, I came across a story about two philosophers discussing the roundness of the earth. One of them believed that the world was round and floating around other celestial bodies while the other believed that it was mostly flat and laid across the back of a turtle.

On further digging, you’ll find that quite a few writers and philosophers credit William James with the line of questioning as the first philosopher in the story. The second was apparently a skeptical old lady.

Here’s the latest record I could find, from John R. Ross of how the conversation might have gone:

The following anecdote is told of William James. [...] After a lecture on cosmology and the structure of the solar system, James was accosted by a little old lady.

"Your theory that the sun is the centre of the solar system, and the earth is a ball which rotates around it has a very convincing ring to it, Mr. James, but it's wrong. I've got a better theory," said the little old lady.

"And what is that, madam?" inquired James politely.

"That we live on a crust of earth which is on the back of a giant turtle."

Not wishing to demolish this absurd little theory by bringing to bear the masses of scientific evidence he had at his command, James decided to gently dissuade his opponent by making her see some of the inadequacies of her position.

"If your theory is correct, madam," he asked, "what does this turtle stand on?"

"You're a very clever man, Mr. James, and that's a very good question," replied the little old lady, "but I have an answer to it. And it's this: The first turtle stands on the back of a second, far larger, turtle, who stands directly under him."

"But what does this second turtle stand on?" persisted James patiently.

To this, the little old lady crowed triumphantly,

"It's no use, Mr. James—it's turtles all the way down."

— J. R. Ross, Constraints on Variables in Syntax, 1967

I love this story. It was one of the first observations of what I called “lazy skepticism” that illustrated how confidence and evidence can feel the same for some people.

What’s interesting about this story is that, to most of us, this lady seems so obviously lazy in her thought. She never considered the consequences of the infinite regression in her argument. In other words, her sentence had an ending, but her concept continued indefinitely without ever being completely defined.

The lady is being lazy, right? The problem with believing the lady is lazy is that we see this sort of issue in many other areas of life.

For instance, if the big bang created everything then what created the big bang? Or how about deciding if it was the chicken or the egg that came first?

Ultimately, our whole world is built on these turtles. We reach out, we study, we test, and then we understand only a little bit at a time.

At first, we thought the earth was flat. Wrong.

Then, we thought the earth was a sphere. Wrong again.

Today, we know that the earth is an “oblate spheroid,” which is like a sphere, but it’s not perfect. I know that seems like an insignificant detail, but these seemingly insignificant nuances actually have significant impacts on patterns that we observe on earth—like weather and tides. So, we recognize them.

Isaac Asimov goes on about this in his book “The Relativity of Wrong.”

So, let’s try to define “wrong” for a minute.

Science is never perfect and it’s constantly moving in the direction of truth. We test, we learn, we test differently, we learn again. The problem is when we believe that the current evidence available is all we’ll ever need to decide that something is true.

The general public doesn’t like this uncertainty. Most of us just want a clean answer. The idea that the world isn’t black and white really disturbs most of us. We want to believe that cops are good and robbers are bad. The world is just easier to navigate that way.

Why Society Rejects The Relativity Of Wrong:

First, nutritionists say that eggs are bad because they have cholesterol. Then, we find out that eggs are good because it turns out that some cholesterol is good. Then, we’re told that eggs are bad again because the good cholesterol is canceled out by the bad cholesterol?

“Those scientists have no idea what they’re talking about! I’m going to eat as many eggs as I want. What a bunch of flip-floppers!”

Wrong again . . . again. Evolving your viewpoint is hard. But Science isn’t “wrong.” Science is based on changing your beliefs based on the facts. Science is the eternal journey for the truth. Science starts with questions that lead to more questions—and it’s this eternal, bifurcating line of questioning that moves us forward in technology, policy, and medicine.

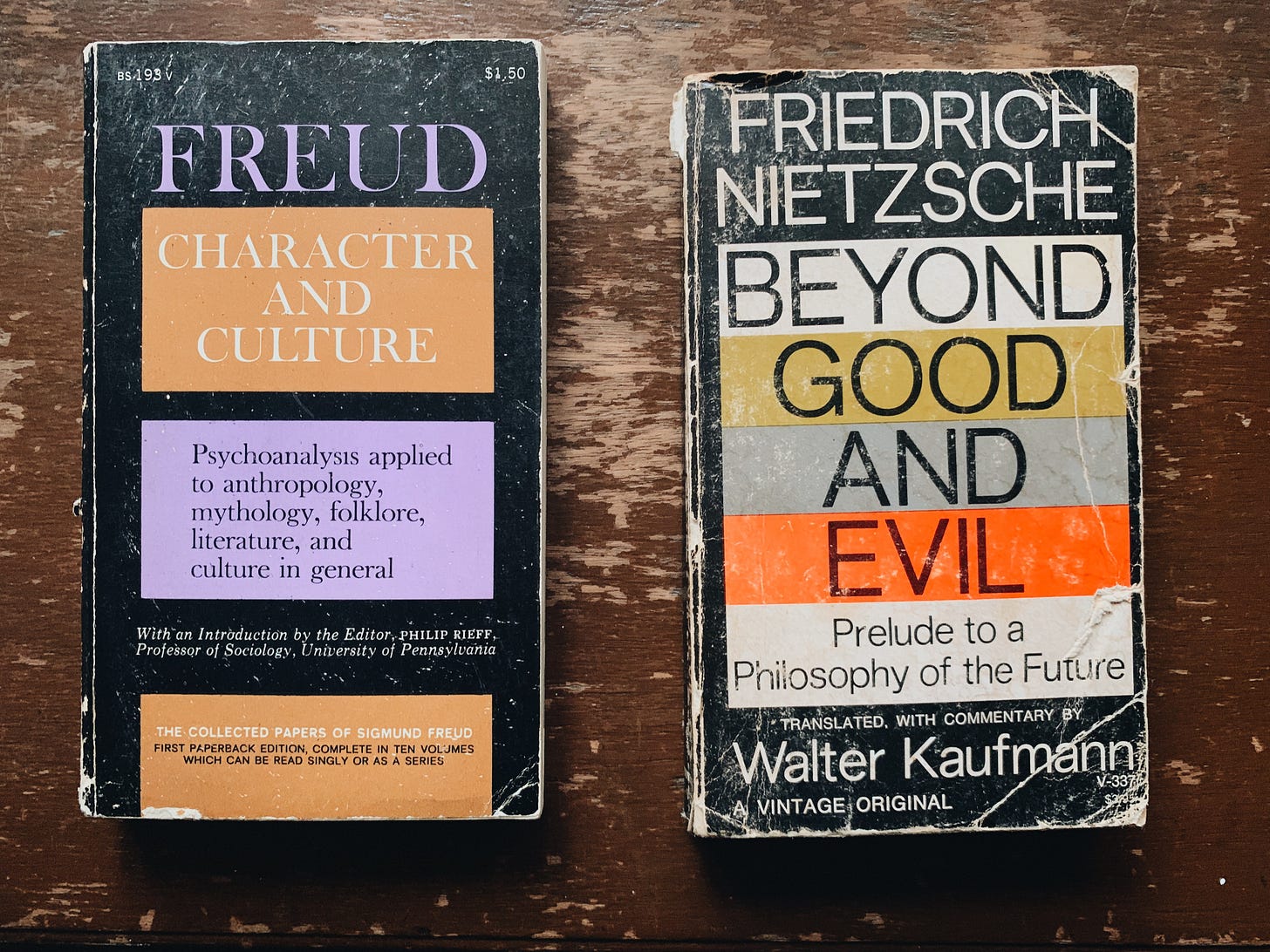

Let’s beat up on Freud for a minute. Freud was wrong about a lot of things. We know that now. But at the time, his approach to psychology and therapy was innovative and challenged the status quo. This means that while we would never use his pure approach today, he created a new foundation for systems of therapy for the field. What he did was “wrong” but had tremendous value for the foundational development of psychology.

Nietzsche made a similar impact on philosophers. In his book “Beyond Good And Evil,” he challenged the status quo that a “good” person was the opposite of a “bad” person—instead positing that they both were subject to the same patterns of thought and that they only expressed those thoughts through different actions. Today, his philosophy still cleaves the reductionist idea of “black and white” thinking from the context of modern lives. But not many people get very far when reading his books because these challenges violate existing beliefs.

As much as people say they believe in challenging the “status quo,” when someone says “God is dead” they just yell “blasphemer! Non-believer!” No one opens their beliefs up to scrutiny and attempts to defend them. They just roll their eyes and walk away. How could God be dead?

So what do we do?

We have no choice but to constantly adjust the course based on new information. It will never mean that we’re 100% right, but it will also mean that we are getting further and further away from 100% wrong.

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

―Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes

It’s our job to disconnect ourselves from our emotional beliefs. It’s our job to constantly evaluate the evidence. It’s our job to open our beliefs to criticism and defend them with evidence. It’s our job to adjust the course as we go and to accept that we are somewhat right and somewhat wrong at all times.

Accepting this is scary because it jeopardizes the foundation of many other systems on which we’ve built our lives—like legislation, government, and religion—but what’s worse, is living on this cracked foundation forever.

If you believe something to be true, I challenge you to look for evidence that someone has debunked it. I bet you won’t look in the hard places.

It’s your job to do the difficult work of putting yourself in a position of defending your thoughts, not just believing in them and scoffing at others’. This is basically 105% of what Twitter is right now. No thoughtful inquiry. Just shooting from the hip and scrolling to the next headline.

Lazy Skepticism is when you say you don't believe something because you haven't seen the "evidence" but you make no effort to debunk your own beliefs and continue believing your old, dated beliefs anyway.

It turns out, that just believing in your old ideals while shunning the non-believers is what’s lazy, after all.

This is a great post, and needed right now. I never put a name to it before, but we really do hear a lot of lazy skepticism now. It’s understandable why. There’s just so much information, and we never got the kind of education we needed to help us parse all of it out as it’s volume increased exponentially.

It presents a problem the focus. We need to decide when we’re going to focus, and dig in to these really tough, dense mounds of information, and see what we can sort out.

One of the most helpful things that I found is to ask a question about method. So, for the example of cholesterol studies, you can ask the question of what method they used to figure out what was good versus what was bad. A knowledge of statistics is also extremely helpful for many of these popular study results. Just understanding sample size, demographics, standard deviation‘s, and the like. Also understanding P values. But by and large, we don’t tend to get an education on those things at the same time as we are hearing about the results.